Introduction

Insurance is defined as a “system to make large financial losses more affordable by pooling the risks of many individuals and business entities and transferring them to an insurance company or other large group in return for a premium.”[1] A multitude of sources not only define insurance terminology but provide educational opportunities as well. However, the business of insurance is generally poorly understood by those who do not work directly within the industry.

Consider, for example, a new consumer’s perspective of establishing a new relationship with a company for auto or homeowners insurance. Many first-time buyers of personal insurance are in their late teens or early twenties. They know that in order to drive off the lot or to get through closing, they need a policy and in some cases, this may be all that they know.[2]

Determining whether to accept a new customer is part of underwriting. The underwriting process is designed to ensure that the expected financial risk to the company as presented by new customers does not exceed the price of the policy. Once a policy offer by the company is accepted by the applicant, the relationship between the insured and company is governed by the contract issued by the company to the insured. Multiple decision points exist throughout the initial and renewing policy terms to ensure that the risk originally accepted remains acceptable to the company, and if not, that appropriate underwriting action be taken.

The complexities in the underwriting process of the personal lines insurance industry are to a great extent based upon the contract and compliance with various categories of laws. The affects of legal requirements as they apply to insurance consumers are found throughout all decision points of the underwriting process, which is first presented from the contractual perspective to serve as a comparison to the changes made to be legally compliant.

U.S. P&C Personal Lines Insurance Underwriting Process – Contractual Perspective

The life cycle of the underwriting process includes these steps:

- An applicant requests a quotation or a policy.

- When the risk is not acceptable, the agent or a company underwriter would so advise the applicant and the process would stop. Until a policy has been issued, the company has no contractual obligations towards the applicant. The risk may become acceptable if the applicant accepts a premium increase by:

a. application of a surcharge

b. placement in a higher rating tier

c. placement in an underwriting company with a higher rating structure as compared to the company that received the applicant’s request, or

d. partial acceptance of the coverage request. For example, if an applicant requested towing coverage for a vehicle for which several towing claims were recently made, the policy may be acceptable so long towing coverage was not included for that particular vehicle.

These four decisions are types of an “adverse underwriting decision”, which refers to any decision in which the consumer is told “no” in any fashion. “No, we won’t offer you a lower price” is why a surcharge or placement in a higher rated tier or company is adverse. “No, we won’t offer everything you requested” is a restriction of requested coverage, and “No, we won’t offer a policy to you” is a refusal to issue.

- When the risk is acceptable or made acceptable, the application will be rated, a quotation provided, and an offer to insure is made. The offer may be good for a short time, perhaps a week. Should the applicant not request coverage during this time, the underwriter may flag the file to follow-up with the applicant shortly before a competitor’s policy would expire (“x”-date follow-up) six or 12 months in the future. When the applicant accepts an offer to insure, a policy will be issued.

- By contract, a newly issued policy may be cancelled within a specified period of 30-60 days from the inception date. Companies want to retain newly acquired business but reserve the right to cancel should additional information be received which, if known before offering to insure would have resulted in the offer not being made. Cancelling a policy for underwriting reasons is another type of adverse underwriting decision. When an applicant did not fully disclose the driving record of all drivers to be rated on the policy, the underwriter may elect to cancel the policy rather than continue. Or the policy may be acceptable if the insured agrees to an increased premium or a coverage restriction. By contract the insurance company must send a written notice to the insured which conforms to contractual provisions when making an adverse underwriting decision.

- The insured is contractually obligated to make timely and adequate premium payments to maintain the policy. When adequate and timely payments are received by the company, the policy will continue. Otherwise, the policy would be cancelled based upon the contractual provisions regarding cancellation for nonpayment of premium.

- Insureds have the right to request cancellation of the policy at any time. When an insured requests cancellation and the risk is acceptable to the company, the company may attempt to keep the insured as a customer. If successful, the policy will continue and if not successful, the company will cancel the policy and may set an “x”-date follow-up.

- Insureds may requests policy adjustments during the policy term. When there are no underwriting concerns with the policy or the request, adjustments will be made as part of routine servicing of the policy. Also during the policy period, the company’s claim department may provide information about the insured or the insured property to the underwriting department. If the information forwarded by the claim department is not judged to materially change the risk, the information would be noted in the file but no further actions would be taken. An underwriter will review requests to adjust the policy and information provided by the claim department. When the characteristics of the policy, the adjustment request, or the information from the claim department is not acceptable to the underwriter, a review of the contract takes place to determine if an adverse underwriting action may be taken. If permitted by contract, the underwriter may elect to send an adverse underwriting notice at that time. If the risk is not acceptable but the contract does not permit action at that time, any changes requested by the insured may still be made.

- The last type of adverse underwriting decision to be discussed is not renewing a policy, which is contractually permitted so long as sufficient notice is given to the insured. Before the expiration date of the policy, a review of the policy for continued acceptability will be made. When it is determined that the policy is no longer acceptable as written, written notice of nonrenewal, adverse modification, surcharge, tier placement, or company placement needs to be sent to fulfill the contract. If the policy is continued, either as is or after certain adverse underwriting decisions, it is rated and a renewal offer is sent to the insured.

The underwriting process starting at step 5 then repeats until the policy is terminated, either by the customer or the company. The link below is a graphical illustration of this entire cycle.

Figure 1 – Underwriting Process – Contractual Perspective

The effects of complying with the major categories of laws on the underwriting process follow.

U.S. P&C Personal Lines Insurance Underwriting Process – Contractual and Compliance Perspective

The contractual perspective of the underwriting perspective is simple when compared to the changes required to comply with federal and state laws that affect the business of insurance.[3] Federal laws generally apply to entire industries or identified activities. These two federal laws have a significant impact on the personal lines underwriting process.[4]

- U.S. economic sanctions, administered by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). The emphasis on compliance with OFAC sanctions increased greatly following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 on U.S. soil. OFAC regulations affect the underwriting process by prohibiting financial transactions with individuals named on government sanction lists.

- The Fair Credit Reporting Act, as administered by the Federal Trade Commission. The FCRA, enacted in 1970 and last amended in 2010, affects the underwriting process when consumer reports are used in the underwriting process.

Each state has unique requirements but the focus here is on laws that are common to most states (with two exceptions). To further narrow the focus, the illustration is limited to personal auto insurance although it would generally apply to all personal lines policy types.

The categories of state laws that significantly affect the underwriting of personal auto insurance are:

- Generalized rating and service laws, referring to requirements that affect how a risk is rated or how service to the applicant/insured is provided. Many of these requirements are derived from the National Association of Insurance Commissioner’s (NAIC) Model Act 880 – the Unfair Trade Practices Act. Introduced by the NAIC in 1947, the Act prohibits unfair discrimination between similar risks and offers other protections. All states have adopted this model act, at least in part.[5]

- Underwriting, referring to the initial determination of risk acceptability and continued acceptability. All jurisdictions regulate adverse underwriting decisions of auto insurance, although the specific application varies (as to how restrictive or permissive the law is, the number of days notice required, type of mailing, etc.).

- Privacy and Underwriting combined, based on the 1980 NAIC Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Act, Model 670, and applied to P&C insurance by 13 states.[6] The Act requires that insurers notify consumer of privacy rights and specific notices associated with adverse underwriting decisions.

- Privacy based on the state insurance privacy laws required by the Gramm-Leach Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999. Forty states used NAIC Model Act 672, the Privacy of Consumer Financial and Health Information Regulation.[7] The Act requires that insurers notify consumers of privacy rights and to take certain actions based on choices made by consumers.

- Residual market or assigned risk plans provide basic insurance coverages for applicants who cannot obtain coverage in the voluntary market. All locations have some variation of a residual market.[8] Two states (New Hampshire and North Carolina) have reinsurance facilities which require insurers to service risks that the insurer would not voluntarily provide coverage for while the state is the reinsurer. Both states also have “take-all-comer” requirements – an insurer must accept an applicant and cannot terminate coverage for underwriting reasons.

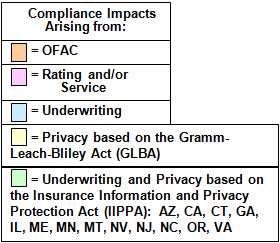

How these laws affect underwriting is discussed in general terms. The affects of each unique state law have their own complexities in procedures, notices, training, etc., and the specific details of each requirement are intentionally undeveloped. The color key below identifies these laws throughout the various steps of the underwriting process.

How these categories of laws affect underwriting is presented in a time sequence begining with a new applicant requesting a policy and ending with the policy being renewed. All of the individual sequences are part of the underwriting process and are used as to graphically display the entire process with the color coding above. The first category to discuss is economic sanctions.

How these categories of laws affect underwriting is presented in a time sequence begining with a new applicant requesting a policy and ending with the policy being renewed. All of the individual sequences are part of the underwriting process and are used as to graphically display the entire process with the color coding above. The first category to discuss is economic sanctions.

U.S. Economic Sanctions (OFAC) Compliance – Confirming Consumers Are Not Sanctioned on U.S. Government Lists

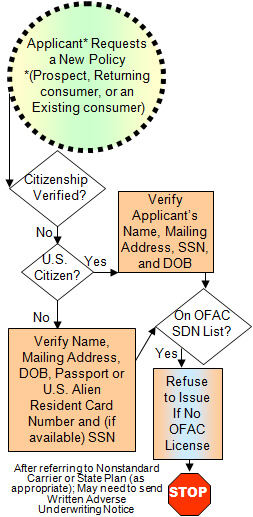

This process starts when an applicant contacts an insurer, or an agent of the insurer, and requests a quotation for a policy. From the insurer’s perspective, applicant means someone who:

- has not had a previous relationship with the insurer,

- obtained quotations or insurance with the company in the past but presently does not have any active business, or

- an active policyholder who is requesting a quotation for a new policy.

The U.S. Treasury, through its Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), requires all American citizens and businesses to confirm that all persons they do business with are not named on government lists of sanctioned individuals. This may be done by collecting from applicants the same information that appears on the government lists: name, date of birth, address, Social Security Number (SSN), and the number and issuing country for a passport. This information would then be used to screen the applicants against the lists.

All U.S. citizens are required to have a SSN. Some but not all non-U.S. residents of the United States have been issued Social Security Numbers.[9] Simple collection of the SSN of all applicants having a SSN will not necessarily lead to compliance with OFAC requirements. Validation edits in the SSN field to prevent collection and reliance on duplicate numbers, invalid numbers, or number combinations that have not or will not be issued are needed[10]. If the applicant is not a U.S. citizen and does not have a SSN, then the passport information should be obtained to screen against the government lists.

When after screening there is a positive match, then financial transactions between the insurer and applicant is prohibited unless a license is obtained from OFAC before proceeding with the transaction. Declining a risk is typically an underwriting function; however, according to OFAC, a declination in this case would be based on an Executive Order addressing foreign affairs which preempts state insurance laws.[11]

Figure 3 is a picture of the underwriting process with respect to an applicant requesting a quotation for a policy and compliance with OFAC requirements.

Consumer Report Compliance

Consumer Report Compliance

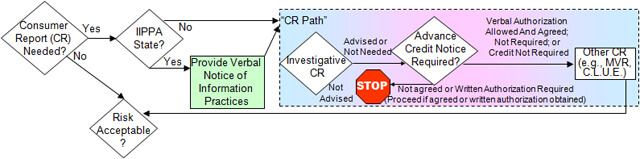

Once it is determined that an applicant and all other prospective insureds are not sanctioned by OFAC, or if sanctioned but a license was obtained from OFAC, the next process is determining if a consumer report will be used to underwrite the policy. Typical examples of the types of consumer reports used in personal lines insurance are investigative consumer reports, insurance scores, motor vehicle reports (MVR), and loss history reports (often generically referred to as a C.L.U.E. report, or Comprehensive Loss Underwriting Exchange). Two laws affecting privacy, rating, and underwriting need to be addressed.

The Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Act (IIPPA) requires that before personal information about a consumer is obtained from a source other than the consumer or a public database that the insurer is to apprise the consumer of rights available under the act. To comply with this requirement for applicants who do business over the phone when a consumer report will be ordered, a verbal scripting of these rights is required. The Fair Credit Reporting Act permits insurance companies to obtain a consumer report when the report will be used in the underwriting process with an individual consumer.

The next phase of the underwriting process is determining if the risk is acceptable.

The next phase of the underwriting process is determining if the risk is acceptable.

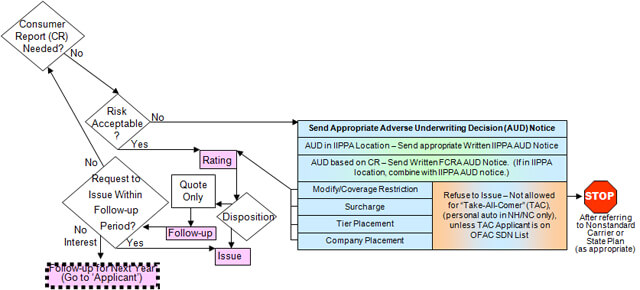

Quoting and Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

The same three outcomes when determining acceptability exist: acceptable as is, acceptable with modifications, or not acceptable. The first two outcomes result in the risk being rated. The last two outcomes require written notice of an adverse underwriting decision.

Two states require insurers to offer auto liability insurance to all who request it because such coverage is mandatory (often called a “take-all-comer” (TAC) requirement). Insurers may not refuse a TAC under state law. However, OFAC has issued an opinion that an insurer must refuse to write any request for insurance from for anyone on a sanction list or to obtain a license from OFAC before writing the policy. The Fair Credit Reporting Act requires notice when the adverse underwriting decision is made, in whole or in part, upon information contained in a consumer report received from a consumer reporting agency. IIPPA requires notice when the adverse decision is made regardless of whether a consumer report was relied upon. The wording of an adverse underwriting notice is dependent upon:

- whether the individual consumer is named on an OFAC list

- the type of policy

- whether a consumer report was used

- where the consumer resides

- provisions of the state’s version of the Unfair Trade Practices Act and any other applicable state laws, and

- the contract between the insured and the insurance company.

When a quotation is provided and an offer to insure is made, the consumer will decide to accept the offer or not. When the offer is not accepted, many insurers will follow-up. When the consumer ultimately agrees, it may be necessary to order consumer reports.

Figure 5 shows how all this fits together.

If a request is made to issue the policy, then determining which written privacy notice or notices must be sent needs to be determined next.

If a request is made to issue the policy, then determining which written privacy notice or notices must be sent needs to be determined next.

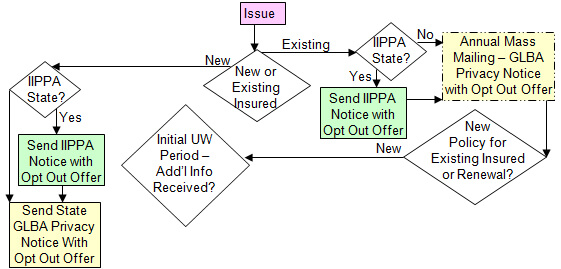

Consumer Privacy Notice Compliance and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Insurers send consumers a privacy notice to comply with the requirements of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) privacy provisions. IIPPA has separate privacy provisions than those of the GLBA. In an IIPPA location, the consumer will receive both the GLBA and IIPPA privacy notices if the insurer does not voluntarily extend IIPPA privacy rights to consumers outside of IIPPA states.

GLBA requires the notice be given to all new consumers and then annually thereafter. However, it would not be necessary to send an additional GLBA notice to an existing consumer. IIPPA requires the notice to be provided with each new policy and also at least annually with renewal policies.

While a company may simply provide the GLBA notice with every new policy, there are consequences to doing so. There is an expense associated with printing, paper, postage, etc. More practically, a company may not legally alter its data sharing practices without having first notified all affected consumers. This means that if the company relies on its annual GLBA notice, it could time changes to when the mass mailing is sent. If, however, the company routinely sends a GLBA notice, then it would have to send an off-cycle notice, thereby changing the date of the mass mailing. From a consumer perspective, there could be several notices received in the mail addressing privacy matters.

Once the privacy notice process is complete, the company enters into the initial underwriting period in which it may re-assess its risk decision.

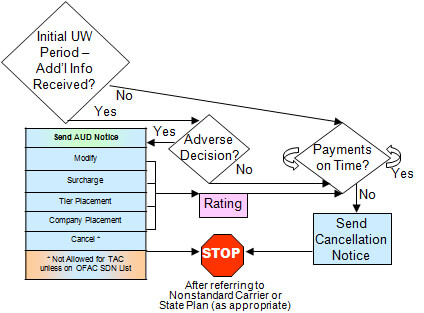

Initial Underwriting Period Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Initial Underwriting Period Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Some companies avoid the expense of consumer reports when preparing a quotation. If the applicant decides not to buy a policy, this expense is not incurred. Most locations allow insurers a set amount of time, typically 45 or 60 days, in which to evaluate its risk decision. For insurers that wait to order consumer reports until after a policy has been issued, the company evaluates the information provided by the consumer report and determines if the risk is acceptable. The outcomes are the same as before: acceptable as is, acceptable with modifications, or not acceptable. Once again, the first two outcomes result in the risk being rated. The last two outcomes require written notice of an adverse underwriting decision.

When the policy is continued, either as is or following an adverse underwriting decision, the insured is contractually obligated to make timely and adequate premium payments to maintain the policy. This is a continual process occurs which occurs throughout the life of the policy. When appropriate amounts are timely received by the company, the policy will continue. Otherwise, the policy would be cancelled in accordance with the contractual provisions regarding cancellation for nonpayment of premium.

The next process, which is also continuous, encompasses insured’s requests to cancel the policy, making decisions regarding consumer requests for policy changes and/or communication from the company’s Claims Department that may be made during the life of the policy.

The next process, which is also continuous, encompasses insured’s requests to cancel the policy, making decisions regarding consumer requests for policy changes and/or communication from the company’s Claims Department that may be made during the life of the policy.

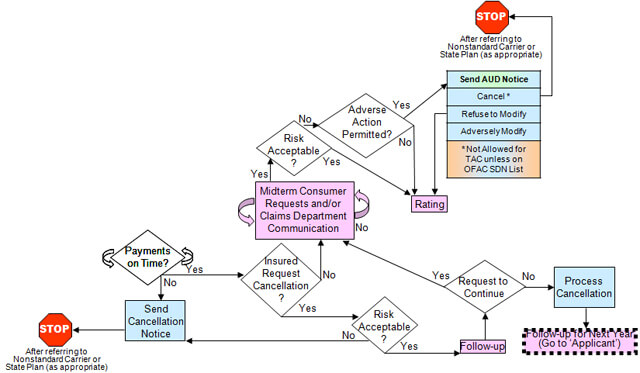

Consumer Requests (Policy Cancellation or Policy Adjustments), Claims Department Communications, and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

An insured may request to cancel the policy at any time during the policy term. If the company’s experience with this consumer is favorable, the company may attempt to change the insured’s decision. If this effort is favorable, then the policy is allowed to continue. If not, then the policy is cancelled and any unearned premium must be timely returned. If the company’s experience is not favorable, then the request would likely be fulfilled without any further action or follow-up. Also throughout the life of the policy, the insured may make requests or the company’s claims department may send notices to the underwriting department. The request or the information provided has to be evaluated, after which it may be determined that request or information means the risk is acceptable as is, acceptable with modifications, or not acceptable.

The first two outcomes result in the risk being rated. The last two outcomes require written notice of an adverse underwriting decision, if the laws of that jurisdiction permit sending notice at this time.

If the policy is continued, the next process is the review of the risk to determine continued acceptability before the company agrees to renew the policy.

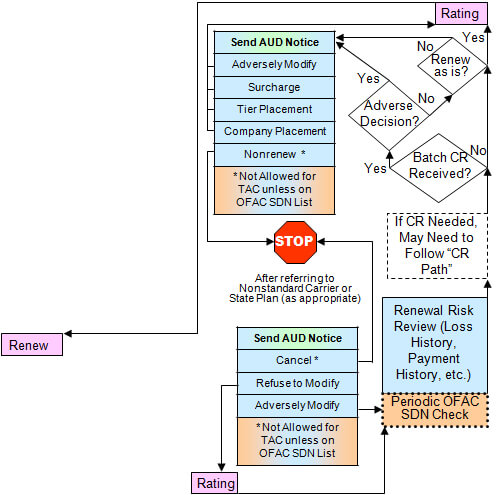

Periodic OFAC Compliance, Renewal Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Periodic OFAC Compliance, Renewal Risk Acceptability and Adverse Underwriting Decision Compliance

Periodically, OFAC expects that businesses check the government lists again to validate that there are no matches. This may be done as often as determined by the company to be prudent, but it is likely done before a policy renews or paying a claim. Renewal risk reviews are usually completed by insurers before each policy renewal, regardless of the periodic OFAC review. Insurers typically check all insureds’ experience with the company. Unfavorable factors, such as a poor payment or loss history are considered. If it is decided to obtain a consumer report, it may be necessary to provide the appropriate notifications before doing so.

If a consumer report is obtained, it must be evaluated with sufficient time to send a notice of adverse underwriting, if that is the ultimate decision. Any information provided by the company’s claims department is evaluated during this review also. Once again, the outcome of the evaluation is acceptable as is, acceptable with modifications, or not acceptable.

The first two outcomes result in the risk being rated for an offer to renew the policy. The last two outcomes require written notice of an adverse underwriting decision, if it is permitted to send notice at this time.

If the policy is continued, it is then rated and renewed.

The final process is determining which privacy notices to send with the offer to renew the policy.

The final process is determining which privacy notices to send with the offer to renew the policy.

Renewal Consumer Privacy Notice Compliance

As previously noted, if the GLBA notice was already sent within the past year, it is not necessary to send it for the renewal of this policy. However, the IIPPA notice must be sent with the policy at least annually.

From here, the cycle continues throughout the life of the policy. While this may not be the exact steps or sequence of steps that are followed from company to company, this presentation shows the essential processes and complexity of personal lines insurance underwriting.

The link below shows how all of these processes fit together into a cohesive flowchart.

Figure 10 – Underwriting Process – Contractual and Compliance Perspective

Summary

Most insurance consumers believe the business of insurance is difficult to comprehend, even though there are educational opportunities to learn more about insurance. Insurers are bound by the contract issued to insureds and have incentive to maintain positive customer relationships in order to remain profitable. When insurance companies do not abide by the contractual language or fail to comply with statutory requirements, the consequences to the company range from negligible to catastrophic. Additionally, not only consumers but regulators, examiners and auditors, rating agencies, and courts expect insurers to comply with all applicable contractual provisions and regulations.

As demonstrated in the preceding graphs, insurance is made even less comprehensible to consumers and others outside the industry based on changes to processes necessitated to comply with the various laws that affect the business. Although both consumers and companies would benefit from consumers being better informed, when considering the range of regulatory requirements above the contractual provisions, the insurance industry has limited opportunities to simplify its processes so that insurance consumers achieve a level of understanding with any significant depth.

Appendix A: Major U.S. Federal Laws and General Affects on P&C Personal Lines Insurance Companies

|

Citation |

Description |

Federal Authority |

General affect(s) |

| 15 USC 1011 et seq. | McCarran-Ferguson Act | Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – Bureau of Competition | Limits the FTC’s antitrust oversight and stipulates that states are the primary regulator of insurance |

| 15 USC 1681 et seq. | Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) | Federal Trade Commission – Bureau of Consumer Protection, Division of Financial Practices | Must have permissible purpose to order consumer reports; requires notification if consumer report is used in an adverse decision; identity theft protection |

| 15 USC 6701 | Requires licensing of insurance producers | None – state insurance departments regulate producer licensing | All persons involved in selling insurance must obtain a state-issued license |

| 15 USC 7001 | E-SIGN (Electronic Signatures) | Department of Commerce – National Telecommunications and Information Administration, Office of Policy Analysis and Development | Facilitates commerce via the internet by providing for electronic validation of transactions |

| 18 USC 1033; 18 USC 1034 | Crimes by or affecting persons engaged in the business of insurance whose activities affect interstate commerce | Department of Justice – Attorney General | Prohibits persons with a felony conviction involving dishonesty or a breach of trust from working in the insurance industry |

| 18 USC 1956; 26 USC 6050I; 31 USC 5312; also see IRS/FinCEN Form 8300 and IRS publication 1544 | Cash payments over $10,000 | Department of the Treasury – Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) | Requires anyone who receives a cash payment more than $10,000 to report the receipt of same to the IRS (money laundering control) |

| 18 USC 2721 et seq. | Drivers Privacy Protection Act | Department of Justice – Attorney General | Restricts state motor vehicle departments from releasing information from a driver’s license |

| 28 USC Appendix | Federal Rules of Civil Procedure | U.S. District Courts | Procedural rules for District Courts, see especially Rules 26 and 34 (discovery of electronic records) |

| 42 USC 1395y (b)(7)&(b)(8) | Mandatory Insurer Reporting | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | Liability, Self-Insurance, No-Fault Insurance and Workers’ Compensation insurers must report payments made to Medicare beneficiaries |

| 42 USC 3604; 42 USC 3605 | Fair Housing Act | Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) | Prohibits redlining in the sale of insurance for homes in the HUD program |

| 42 USC 4001 et seq. | National Flood Insurance Program | Department of Homeland Security – Federal Emergency Management Agency | Provides insurance for the peril of flooding for owners and tenants of real property |

| 47 USC 227; 47 CFR 64.1200; 47 CFR 64.1601; FCC 03-153 Appendix A, 16 CFR 310 | Telemarketing Sales Rules – National “Do Not Call” Registry | Federal Communications Commission – Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau | Restricts the circumstances when marketing calls may be made |

| 49 USC 30502; 49 USC 30504; 49 USC 33109; 49 CFR 544 et seq. | Stolen, junked, and salvaged vehicles | Department of Transportation – National Highway Safety Administration | Selected insurers must report title information about stolen, junked, and salvaged vehicles to the Secretary of Transportation |

| 49 USC 33110; 49 USC 33112 | Passenger motor vehicle information database | Department of Transportation – National Highway Safety Administration | Insurers must report information regarding premiums, damage susceptibility, crashworthiness, degree of difficulty of diagnosis and repair of damage to, or failure of, mechanical and electrical systems |

| 50 USC App. 501 et seq. | Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA) | Department of the Treasury – Office of the Comptroller of the Currency | Provides protections for active duty military personnel including a reduction of interest on loans (affects premium financing) |

| 31 CFR 103.170 | Anti-Money Laundering Program | Department of the Treasury – Office of the Comptroller of the Currency | None – exempts property and casualty insurers from the requirement to have an anti-money laundering program |

| 31 CFR 210 et seq. | Automated Clearing House (ACH) | Department of the Treasury – Bureau of Financial Management Service | Regulates ACH entries with the electronic funds transfer (EFT) system |

| 45 CFR 160 et seq. | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) | Department of Health and Human Services – Office for Civil Rights | Provides requirements to obtain, use, and store health information |

| 50 USC Appendix Sec. 5; 31 CFR 103; HR 1268, Section 202 (CFR 23); 31 CFR 500 et seq.; 501 et seq. (See also U.S. Treasury Bulletin, “Foreign Assets Control Regulations and the Insurance Industry”, 4/29/04) | Trading with the Enemy Act and Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) Requirements | Department of the Treasury – Office of Foreign Assets Control | Requires: (1) insurers to confirm that prospective employees, customers, and business partners are not on government sanction lists before engaging in financial transactions with these individuals or businesses; (2) periodic confirmation that active employees, customers, claimants, and business partners are not on government sanction lists; and (3) prohibits transacting business with individuals from specified countries |

| § 8B2.1 | Federal Sentencing Guidelines | United States Sentencing Commission | Requirements for an effective Compliance and Ethics Program |

| The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203 | Federal Insurance Office | Department of the Treasury | Monitors all aspects of the insurance industry. Coordinates and develops policy relating to international agreements. |

Appendix B: Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Act State Populations[12]

|

April 1, 2010 Population Estimates |

||

| IIPPA States | Population | |

| 1 | Arizona | 6,392,017 |

| 2 | California | 37,871,648 |

| 3 | Connecticut | 3,574,097 |

| 4 | Georgia | 9,687,653 |

| 5 | Illinois | 12,830,632 |

| 6 | Kansas | 2,853,118 |

| 7 | Maine | 1,328,361 |

| 8 | Minnesota | 5,303,925 |

| 9 | Montana | 989,415 |

| 10 | Nevada | 2,700,551 |

| 11 | New Jersey | 8,791,894 |

| 12 | North Carolina | 9,535,483 |

| 13 | Oregon | 3,831,074 |

| 14 | Virginia | 8,001,024 |

| Total IIPPA | 113,690,892 | |

| US | 308,756,648 | |

| IIPPA | 36.8% | |

Joseph L. Wiest, CPCU, ARC, ACP, is a corporate compliance director of market conduct with a top ten P&C insurance group. He is a graduate of the University of Nebraska, having earned a B.S. in business administration. Since 1984, he has been employed in the insurance industry, working 20 years for a major personal lines direct writer, holding positions in customer service, line underwriting, staff underwriting, and compliance. He also served as the compliance officer of a nonstandard auto carrier for two years. He has earned a business ethics certificate from Colorado State University in addition to nine other professional insurance designations.