Introduction

The property and casualty insurance policies that most Americans buy depend on a system by which insurers file rates—the fees they charge for insurance policies—and forms—the language and forms insurers use to describe those policies to consumers. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have separate laws concerning these rates and forms. Increasingly, these rates and forms flow through a computer program called the System for Electronic Rate and Form Filing (SERFF), which is owned and operated by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). Nineteen states require that all filings go through SERFF.

This article explains the System for Electronic Rate and Form Filing’s structure and raises questions regarding its usefulness. The article’s first section provides a broad overview of the “admitted” or “standard” insurance market, and describes why rate and form filing are essential to its continuation in its current form. The second section describes the history and function of SERFF. The third section discusses three major problems with SERFF. The fourth and final section proposes a series of solutions that would solve these problems. SERFF, as it currently exists, raises serious practical, equity, and legal questions—particularly relating to the delegation of taxing authority—and needs reform.

Rate and Form Filing: The Admitted Market Described

Most Americans buy insurance in the “admitted” or “standard” market. Two fundamental features distinguish this market from the “non -admitted” or “excess and surplus” (E&S) market: “utmost good faith” sales and a near certain guarantee that claims will be paid. These two features imply a level of third-party oversight of rates and forms.

Utmost good faith refers to the circumstances under which nearly all insurance policies are sold. Essentially, it means that buyer and seller agree to disclose all pertinent information to each other in an honest and forthright fashion. Insurance consumers must disclose all pertinent risk information to their agents and agents must provide accurate, straightforward, common sense descriptions of the products they are selling. Agents do not have to perform detailed investigations of their customers’ lifestyles and risk factors and consumers do not have to understand every legal detail of the policy language. In other words, when a customer tells an agent that a roundtrip commute is 40 miles, the agent can simply assume that is true. When an agent tells a customer that a policy will cover theft from a car, the customer can rely on thefts, as they are commonly understood, being covered.

A regime of utmost good faith contracts in a common law system requires broad consensus on the meaning of specific contract terms. To facilitate standardization, a private, national organization called the Insurance Services Office (ISO) maintains standardized forms that serve as the basis for almost all insurance policies.1 All states have different laws governing insurance, so these general standard forms must be modified for every state. Different companies, furthermore, modify these forms to gain a competitive advantage or to serve their customer base. (For example, one auto insurer that began by serving government employees continues to provide special discounts for most people who work for the government, while another insurer that focuses on the military provides special coverage for military uniforms.)

These standard forms require state level reviews in order to bring them into compliance with various state insurance laws. Without such reviews and a broad agreement on the meaning of policy language, any ambiguity or dispute would require significant legal wrangling. Maintaining both state specific insurance regulation and an utmost good faith system requires that someone at the state level check forms for compliance with state laws and regulations, but it does not necessarily need to be government doing so. Form review and regulation can be handed over to private parties—some states, including California and Virginia, contract out some aspects of it.

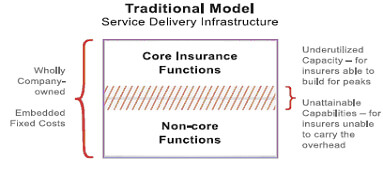

The admitted market also provides a near ironclad guarantee that insurers will pay all legitimate claims. It carries out this guarantee through solvency regulation and a system of state level guarantee funds.

Solvency regulation, also known as actuarial adequacy regulation, is essentially a post facto effort to prevent fraud. It is a way of making sure that companies can actually pay the claims for the policies they write. Since insurance is mainly a promise to pay in the event that something unexpected and adverse happens, companies making those promises must have reasonable assurance that they can keep them. This, in turn, requires that someone oversee insurance company investments—insurers could not, for example, put all their money into penny stocks—and make sure that they charge rates high enough to pay the claims they can reasonably expect. In the excess and surplus market, contracts and detailed examination largely accomplish this. In the admitted market, solvency regulation does it.

Actuarial adequacy regulation requires that someone monitor the rates being charged. This does not mean that government has to approve them or has any authority to say that they are “too high”—in some states, including Illinois, Wyoming, and Vermont, government officials have little or no say over how high rates should go—but it does mean that someone must stop rates from going below the level needed to pay claims. Even states that do not require filing of rates still require that companies keep information to justify their rates open to inspection.

In addition, all 50 states maintain state guarantee funds. With the exception of New York’s fund, these guarantee funds function as industry run associations.2 Insurance companies that want to operate in the admitted market must participate in the guarantee fund. When and if an insurer proves unable to pay its claims, the guarantee fund imposes a special tax, called an assessment, on all companies writing insurance policies in the admitted market. The system certainly implies some moral hazard, but given that insolvent companies face a severe penalty in that their assets are liquidated in full, the moral hazard from guaranteeing payment of their claims does not seem that severe. Guarantee funds do not always assure 100 percent payment of claims and few cover very large claims from very wealthy individuals or business.3

For insurers and consumers who do not feel they need the assurance of the admitted market, it is almost always possible to do business with excess and surplus companies, which do not have to submit their forms or rates to any state authority.

The E&S market is not chaos. In fact, it can—and sometimes does—function a lot like the admitted market. Two parties in the excess and surplus market can swear they will deal with one another on an utmost good faith basis. All states, furthermore, have laws mandating that excess and surplus companies charge adequate rates. Although all excess and surplus lines policies are unique, some relatively common types of policies— coverage of collections of exotic cars, for example—function very much like policies in the admitted market and may even draw on the same ISO forms.4

SERFF and Its Owner

The System for Electronic Rate and Form Filing took on its current form in the mid 1990s. The system, says its owner, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, “is designed to enable companies to send and states to receive, comment on, and approve or reject insurance industry rate and form filings.”5 It does this, but not very well.

NAIC is an unusual organization. It has some aspects of a government entity and some aspects of a private one. On the one hand, NAIC describes itself as a private organization, and has some features of the same. It is registered under section 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Code, does not report directly to any particular government any more than any other non profit, does not need to follow any government hiring and purchasing rules, and is not covered by freedom of information laws. Like other associations, NAIC works to advance the interest of its members, through model legislation and lobbying.6

On the other hand, NAIC has significant government like features. First, all of its members are jurisdictional – usually state -insurance commissioners. Twelve are state wide elected officials and all of the others are reasonably important state level officials. Second, it has some powers that broach on lawmaking, including its administration of large parts of the Interstate Life Insurance compact, which harmonizes life insurance standards and practices around the country and sets technically voluntary “standards for accreditation” to which almost all states adhere. Therefore, NAIC has enough power for it to deserve the same scrutiny that one might apply to a government, especially since it owns and manages SERFF.

How SERFF Works

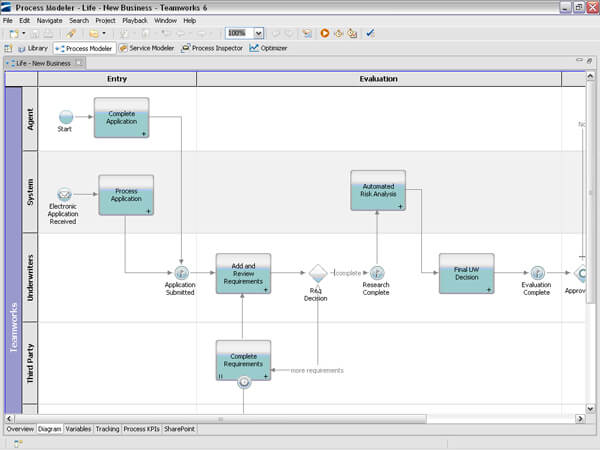

The System for Electronic Rate and Form Filing is a paperwork flow management tool. SERFF creates a universal interface for dealing with correspondence between insurers and insurance regulators. It assigns a unique number to each filing and provides a standardized place to manage correspondence between rate examiners and insurance company employees.7

For more than a decade, SERFF has managed the paper flow for insurers and state insurance departments alike. The training manual that NAIC publishes for SERFF says that the system “promotes uniformity and has the added benefit of supporting the flexibility states need to accommodate their differing requirements and laws.”8 SERFF pursues its first goal by making use of standards – uniform forms and product codes – that NAIC and ISO have introduced and through its administration of the Interstate Life Insurance Compact.9 As noted, nearly everything – including some of the standardized forms – remains subject to state level oversight and changes in order to conform to various states’ laws.

The NAIC’s management – which ultimately reports to state insurance commissioners – has total ownership over SERFF. Currently, a joint industry government board of 13 members – seven from government and six from industry – oversees SERFF. The board requires a supermajority of 10 to make most decisions. However, NAIC has often acted without the board’s approval. In 2007, for example, NAIC introduced a premium tax filing companion to SERFF called OPTins without ever even mentioning it to the board.10 In 2008, the NAIC culminated this trend when it announced plans to take away nearly all of the board’s power and demoted its status to that of an “advisory group.”11

NAIC remains the sole owner of all SERFF trademarks and intellectual property. The system has found widespread adoption. As of early 2009, 19 states mandated its use and all others used it in some respect.12 Every national insurer and every domestic insurer operating in those 19 states must use it and pays its filing fees.

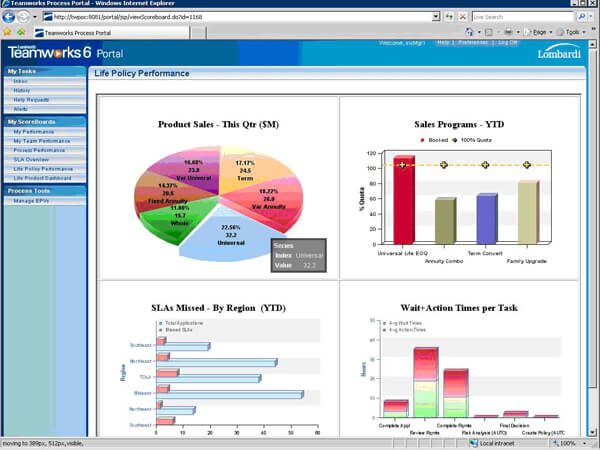

SERFF’s Revenue

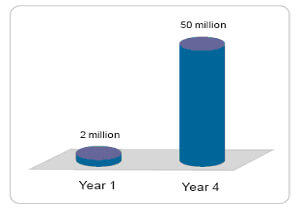

SERFF supports itself through fees paid by the industry; NAIC sets these fees on its own. SERFF sets a standard filing fee of $7 per filing and allows companies to buy “blocks” of filings at prices that can go down to $6 each. State insurance regulators pay no actual fees to participate in SERFF.13 The NAIC and SERFF’s board can vary these fees without any consent from state authorities. Being mandatory, SERFF makes a lot of money for NAIC. Business Insurance Magazine reports: “At a December 2007 SERFF board meeting, the NAIC provided financial data through Oct. 31, 2007, that showed nearly $2.46 million in SERFF revenues and nearly $1.29 million in operating expenses, resulting in a profit of about $1.17 million.”14

During 2007, NAIC’s best year ever financially, this comprised about 20 percent of the $5.5 million in surplus earned by NAIC – what a private company would call profit. For 2008, no hard data are available but it appears that NAIC’s surplus will total only about $120,000 according to industry data made available to the Competitive Enterprise Institute. According to NAIC, SERFF processed over 500,000 filings during 2008 and, charging a minimum of $6 per filing, this would have produced at least $3 million in revenue.15 However, since $6 is only a floor for fees charged, many transactions would have netted more than that.

Problems with SERFF

For as much money as SERFF makes for NAIC, the program does not accomplish its job particularly well. It has rarely been updated, its profits appear to constitute monopoly rents, and its structure may well violate several state constitutions. This section describes the problems.

SERFF is Out of Date. In essence, SERFF is a reasonably simple, customized database application. As a piece of software, it is not complicated or expensive to create. The interface appears to be something that someone familiar with the software could create in a few days with an off- the- shelf rapid development tool such as Oracle’s Application Express.16 (Building and coding queries, however, would take more time.)

SERFF does not fully automate the process of rate filing. Many otherwise standardized – or semi -standardized – forms and supporting data must be submitted via attached PDF documents, rather than through a fully interactive interface.17 The software is not up to date. It uses Microsoft Internet Explorer 6—an eight year old Web browser—as its default client interface.18 Users are advised to use Adobe Acrobat 6, released in 2003, to deal with documents submitted through SERFF. In short, as a computer program, SERFF provides nothing exceptional. SERFF announced no major upgrades to its software during 2008.

SERFF’s value comes from its standardization and the work that state insurance departments – and their industry clients – have put into making their forms available online. Given the software’s enormous profits, it is odd that NAIC has invested so little in it and failed to bring it up to date.

SERFF Is Unfair. The “profit” that SERFF earns is what economists term a “rent” – surplus revenue obtained due to a third party’s interfere in an otherwise mutually beneficial bilateral exchange. As noted, nineteen states require that all filings go through SERFF and thus require insurers to pay NAIC’s fees. These fees would be called taxes were they to flow to state governments. Instead, the NAIC collects the fees and spends the money on purposes that it never fully discloses to the payers. The excess profits can fairly be described as a tax for private purposes since insurers have no choice in many states but to pay them. It is fundamentally unjust to mandate the payment of a tax to a private party. People and corporations deserve choices. The states themselves do not share in NAIC’s revenue from SERFF. The money it earns goes to NAIC, not to the state insurance departments that must pay to comply with it.

SERFF Ought to Raise Constitutional Questions. Several (though not all) states that mandate the use of SERFF have provisions in their constitutions that ought to raise questions about the legality of the system. Many state constitutions allow only the “state” or the “legislature” to collect taxes. Thus, a serious question exists whether SERFF’s fee might be considered an authorized “tax.” The fee, after all, is collected by a private party and set without direct control or oversight by any legislature. Insurers and others who pay SERFF fees may have grounds to launch a legal challenge to the system. Eight states that mandate SERFF filing have provisions that might be used to challenge SERFF.19

- Georgia: “Except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, the right of taxation shall always be under the complete control of the state.”20

- South Dakota: “No tax or duty shall be imposed without the consent of the people or their representatives in the Legislature.”21

- Rhode Island: “All taxes…shall be levied and collected under general laws passed by the General Assembly.”22

- Minnesota: “The power of taxation shall never be surrendered, suspended or contracted away.”23

- New Hampshire: “No subsidy, charge, tax, impost, or duty, shall be established, fixed, laid, or levied, under any pretext whatsoever, without the consent of the people, or their representatives in the legislature, or authority derived from that body.”24

- Massachusetts: “No subsidy, charge, tax, impost, or duties, ought to be established, fixed, laid, or levied, under any pretext whatsoever, without the consent of the people or their representatives in the legislature.”25

- Michigan: “The power of taxation shall never be surrendered, suspended or contracted away.”26

- Oklahoma: “The power of taxation shall never be surrendered, suspended, or contracted away.”27

SERFF Does Not Perform Its Central Function Very Well. SERFF’s central function is to facilitate exchange of information on insurance rates and forms across states, but in some instances, the data exchanged through SERFF seems scanty. For example, in addition to some check boxes, SERFF’s property and casualty rate filing. Web forms require only eight discrete pieces of data – which essentially amount to “How much do you want to charge?” and “How many people will this impact?”28 That sort of data will satisfy few, if any, state regulators alone; all states have regulations beyond this.29 Nearly all states require additional data justifying the rates based on loss experience, impact on the company solvency, fairness to various protected groups, and compliance with numerous other state laws.

Conclusion: A Proposed Solution

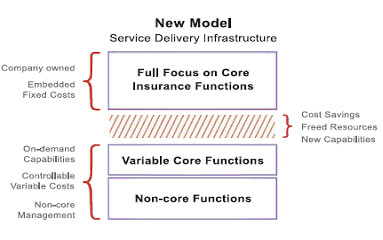

Rather than maintain these mandates, NAIC could best advance its own mission by opening SERFF to competition. In establishing a series of uniform standards for data exchange relating to files and forms, NAIC has done the job most consistent with its non profit mission. However, in earning monopoly rents, failing to update its software, and maintaining a fee structure that may violate some state constitutions, NAIC behaves in a questionable manner. It should strive to improve SERFF for states and insurers alike by separating its functions and creating a flexible “open source” license for SERFF.

As long as NAIC acts like a government in many respects, it merits the same scrutiny and oversight as governments do. A reform process for SERFF would involve three actions:

- Separation of SERFF’s intellectual property from its operations;

- Creation of an “open source” license for SERFF; and

- Allowing free competition between providers of “SERFF standard” software. Essentially, SERFF would become a standard rather than a specific application.

SERFF reform would require splitting SERFF into two entities – at least one of which should be independent of NAIC. The first entity would administer SERFF as it currently exists. It could be a wholly independent, investor owned company, a for-profit subsidiary of NAIC, or some other private entity. As a private company, it would collect all fees owed for SERFF filings under the current system, set its own prices, and be able to do anything else that the law does not specifically prohibit.

Another entity, a non profit consortium independent of NAIC – perhaps controlled by an industry regulator board – would own SERFF’s intellectual property. It would license the SERFF trademark, oversee a “standard” SERFF code base, and certify privately produced software as “SERFF compatible.”

This code base would be governed under an “open source” license.30 Like all open source licenses, it would grant programmers the right to modify, redistribute, and profit from the SERFF source code. Anybody who wanted to create a product and market it as SERFF compatible would have to subject it to a review process overseen by the consortium. (The consortium members could agree to use only products that passed this review process.) The process would provide assurance that various SERFF compatible products could exchange data freely, work with one another, and share common filing tracking numbers. Review fees would fund the consortium’s operations. Such a process has worked for dozens of other Internet applications – HTML/HTTP (for Web pages), MIME (for e mail), Rich Text Format (for word processing documents) – are all “open” standards maintained through consortia. Many parties market and distribute applications that use them and all of the applications, for the most part, work pretty well together. States and companies wishing to depart from the SERFF standard could do so.

The opening of the SERFF source code would solve most of SERFF’s problems. Most importantly, the questions about delegation of tax responsibility would be resolved. SERFF would clearly be a private market product and no state or company would have any specific obligation to pay money to NAIC or to anybody else in particular.31

States and insurers satisfied with the NAIC’s current management of SERFF could continue using the same software they use now. On the other hand, those states and individuals who have problems with the system could choose from a variety of new products that would spring up in the wake of the opening of SERFF’s current business model. Some operators might simply license the product to insurers and allow unlimited use for a flat fee. Others might continue with NAIC’s pay -per- use filing system. Some might charge nothing for the product and make money off of technical support, sales of related products, or even (as is the case with the Linux operating system) the notoriety gained through having developed the product. Since NAIC would no longer have a monopoly on the product, no constitutional questions would exist. As different developers create new applications that serve the same functions as SERFF, people dissatisfied with the old software’s progress could finally take their business elsewhere.

In addition, a more open version of SERFF would bring market forces to bear. Having the choice among multiple ways to file forms and make actuarial adequacy information available would make it easier to create new products within the admitted market. Constitutional questions about the delegation of tax authority would also vanish.

SERFF as it exists does not work, and therefore a better system is worth considering. A competitive, open -source SERFF system would work better than the existing system and would increase freedom for insurers and consumers alike.

This article was originally published May 1, 2009 in issue no. 155 of the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s OnPoint series.

References

1 For example, nearly all homeowners’ insurance policies for single family detached houses get written on the basis of a form called the “HO 3” which covers 16 named perils and everything else that is not specifically excluded.

2 New York has a pre funded guarantee fund managed by the state as an insurance company. Its functioning is, in many respects, similar to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

3 Florida’s insurance guarantee fund is typical. The fund covers claims up to $500,000 for homes and $300,000 for most other claims. See “About FIGA,” http://www.figafacts.com/faq.asp. For another example, New Jersey offers coverage up to $300,000.http://www.njguaranty.org/infoCenter/faq.asp

4 For reasons that lie beyond the scope of this paper—probably related to the transaction costs implicit in duplicating the current features of the admitted insurance market without a governmental rate overseer or mandatory guarantee funds— very few individual consumers choose to buy policies in the excess and surplus lines markets. Most well known insurers do not operate in the excess and surplus lines market and those that do typically do so through subsidiaries that maintain distinctive, independent brand identities.

5 National Association of Insurance Commissioners/SERFF, “About SERFF,” 2008, http://www.serff.com/about.htm.

6 NAIC does much of its lobbying through its D.C. office. NAIC’s major policy positions include opposition to national regulatory modernization for insurance and support for global solvency standards.

7 Ibid, p. 15, pp. 169 224.

8 NAIC, SERFF Version 5: Industry Manual, 2007, p. 4.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Meg Fletcher, “Stoked to Carve SERFF: NAIC Proposal Called ‘Hostile Takeover,” Business Insurance, August 11, 2008.

12 NAIC, “List of States that Mandate SERFF,” http://www.serff.org/index_state_mandates.htm.

13 SERFF rates are not published in any widely available source; industry sources reported the fees. State insurance departments do have some costs. They must have computers to handle SERFF filings and NAIC strongly recommends that they use Adobe Acrobat Professional. Acrobat Pro lists at $160 but is available for $140 on several websites.

14 Fletcher.

15 NAIC, “SERFF Surpasses 500,000 Transactions,” December 6, 2008,http://www.naic.org/Releases/2008_docs/serff_500000.htm.

16 In fairness, Web based Rapid Application Development frameworks did not exist when SERFF’s first version came online.

17 Ibid, p. 94.

18 Microsoft Corporation, “Windows History: Internet Explorer History,” 2007,http://www.microsoft.com/windows/WinHistoryIE.mspx. See NAIC (2007) for requirements.

19 In all of these states, “workarounds” exist that could make it possible for the current system to continue. In the four states that reserve the power of taxation to the legislature, the legislature could simply pass a statute mandating the payment of SERFF fees. However, states that forbid the surrender, suspension, or contracting of revenue collection could face more significant problems—state courts could consider the ability of NAIC to set fees on its own as an instance of “contracting away.”

20 Constitution of the State of Georgia, Article VII, Section 1(I).

21 Constitution of the State of South Dakota, Article VI, Section 17.

22 Constitution of the State of Rhode Island, Article VII, Section 1(I).

23 Constitution of the State of Minnesota, Article X, Section 1.

24 Constitution of the State of New Hampshire, Article 28.

25 Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Article XXIII.

26 Constitution of the State of Michigan, Article XI, Section 2.

27 Constitution of the State of Oklahoma, Article X, Section 5.

28 Ibid, pp. 88 89.

29 Regulators have not specifically complained about this because they typically work to enforce their own state laws.

30 NAIC would likely select a given license from the long list of licenses that have gone through the Open Source Initiative’s Review Process. Open Source Initiative, “Licenses by Name,” http://www.opensource.org/licenses/alphabetical.

31 By way of analogy, consider common law court requirements for the format of legal briefs. Since any decent desk top publishing software can produce the same brief, the requirement does not impose any specific “mandate” or “tax” even though it may impose a burden of sorts.

Eli Lehrer is a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute where he directs CEI’s Center for Risk, Regulation, and Markets. RRM, which operates in both Washington, D.C. and Florida, deals with issues relating to insurance, risk, and credit markets. Prior to joining CEI, Lehrer worked as speechwriter to United States Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R.-Tenn.). He has previously worked as a manager in the Unisys Corporation’s Homeland Security Practice, Senior Editor of The American Enterprise magazine, and as a fellow for the Heritage Foundation. He has spoken at Yale and George Washington Universities. He holds a B.A. (Cum Laude) from Cornell University and a M.A. (with honors) from The Johns Hopkins University where his Master’s thesis focused on the Federal Emergency Management Agency and Flood Insurance. His work has appeared in the New York Times,Washington Post, USA Today, Washington Times,Weekly Standard, National Review, The Public Interest, Salon.com, and dozens of other publications. Lehrer lives in Oak Hill, Virginia with his wife Kari and son Andrew.