Challenges

Insurance companies face many challenges, as competitive pressures mount, regulatory hurdles abound and market cycles oscillate relentlessly. Getting products to market faster, minimizing regulatory and financial risk and lowering operating costs have become universal mandates. The insurance industry, perhaps more than any other, requires leaders to emerge that know how to innovate, that replace the routine with the novel and push the limits of their operations to derive that most elusive of organizational ideals – sustainable competitive advantage. Organizational alignment – the idea that strategic vision, work processes and employee rewards are fine-tuned and in synch – provides the enterprise framework needed to achieve that ideal. This is no faddish methodology or technique of the moment. Organizations that fail to produce a consistent, replicable and scalable architecture are ultimately relegated to the domain of obsolescence. This article provides the practical means to avoid such a fate.

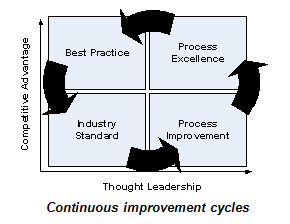

Maintaining competitive advantage requires new levels of thought and the application of a disciplined and systematic way of doing things. What gets a company to one level of success is not sufficient to achieve the next; innovation and genuine thought leadership are called for.

While the thought leader’s job involves painting a picture that promotes some worthy ideal which the rank-and-file dutifully pursue, the substance behind that picture lies in the careful articulation of the strategies chosen, the means by which the good work of the organization is done and a clearly communicated understanding of the rewards earned for the attainment of the organization’s objectives. Taken together, we have a formula for success; the alignment of strategies, work processes and rewards provides a solid framework upon which to build a viable organization for the long term creating, in effect, the glue that binds employees as they work toward the fulfillment of organizational goals.

That group of individuals who work together toward a common purpose has become the Holy Grail of organizational excellence. Maintaining cohesiveness, however, is no easy task; consistently moving people together in a particular direction with the passion, dedication and competence needed in today’s ultra-competitive world requires new levels of commitment and with that, the call for strong leadership is unprecedented.

Implementation

Deploying any enterprise-wide initiative requires first readying the organization for transformation. As such the values, beliefs, norms and policies that characterize the culture must conform to the new way of doing things. Readiness for the implementation of an alignment framework means solid top-down management support, and constitutes a change that to be effectively brought about requires a sense of urgency, a strong vision, genuine empowerment to act and an institutionalization of the new approaches contained in the changed work processes. For change to be sustainable, management support must be complemented with appropriate attention to training and infrastructure:

- Management support. The importance of support from the top cannot be overemphasized. As a principal source of validation, top-down management support is a requirement prior to the launch of any major initiative that involves change.

- Training. Training is the method used to institutionalize the new work processes. In addition to teaching new tools and methods, institutionalization requires formal policies and procedures to be established.

- Infrastructure. Sharing of information and applications across teams is an important element of effective change management. The deployment of a distributed information sharing or knowledge management system greatly assists team members by providing a common repository of “lessons learned” to be applied in subsequent improvement efforts.

To achieve alignment:

- A compelling vision must be developed and communicated to support a strategic focus;

- Uniform work processes must be adopted and applied to create efficiency, reduce role confusion and eliminate the ad hoc approach to work; and

- An effective reward system must be created to tie work processes with strategy to maintain focus.

A compelling vision

Perhaps the single greatest leadership challenge is the creation and effective communication of a compelling vision. What is it that makes a vision compelling? What business purpose could possibly move people to action, simply because it’s a worthy pursuit? How can a leader best communicate in a way that drives people to action? Unfortunately, “vision has become one of the most overused and least understood words in the language,”[i] a vague term with multiple meanings depending upon who’s using it.

Developing the vision

As a foundation for organizational change, the best source of renewed vigor is “a clear and value-based vision created by an appropriate mix of rational analysis, intuition and emotional involvement”[ii] that inspires all to work not just for themselves, but for the good of the company in a way that advances some broader commitment. Max de Pree, retired CEO of Herman Miller, touted the vision of his company “to be a gift to the human spirit,”[iii] providing a lofty image for the company to pursue. To create their own sense of purpose, members of an organization must ask themselves, collectively, “Why are we here?,” as those companies that exhibit greatness, having endured years of challenge and change, tend to embrace a set of common values and promote a solid reason for existing. Representing the company’s distinct ideology, values and purpose remain fixed while the world around it changes, and with it the organization’s strategies and practices that must adapt accordingly.

A compelling vision comprises three distinct aspects. First, those core values common to the workforce must be discovered and embraced; next, a core purpose must be articulated; and finally, the envisioned future must provide excitement about the prospect of meaningfully contributing to its attainment.[iv]

- Discovering core values. Vision begins with an understanding of values common to members of the workforce. According to Bruhn, “Consistent leadership and an espousal of values are the cornerstones of a stable culture.”[v] A brief employee poll that asks what each considers to be their most important values can be quite revealing. Integrity, honesty, providing value, creative expression, professionalism and open communication are typically common values that may be uncovered during such a poll. The three or four that are most often mentioned are values to be embraced and promoted throughout the enterprise as an important foundation of a culture that supports the company vision.

- Discovering core purpose. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of describing a vision is articulating a core purpose – what exactly does the organization stand for? Why does it exist? What is its meaning? Viktor Frankl describes the search for meaning as the primary motivation in one’s life. The effective leader understands the unique and specific meaning assigned to work by each individual, and speaks to the sense of purpose derived from that meaning. Only then does the work “achieve a significance which will satisfy [the individual’s] will to meaning”[vi] – the driving force beyond financial reward that motivates people to action and keeps them interested.

- Envisioning the future. The truly compelling part of an effective organizational vision is a view of the future, embraced by all, toward which they are collectively moving.

Communicating the vision

Once developed, the failure of leadership to consistently communicate the message the vision is designed to inspire will leave members of the organization unmoved and the good work of the organization underperformed. Anita Roddick, founder of the wildly successful Body Shop, describes the importance of communication:

I think that [communication] is one of the most essential skills of leadership. Because no matter how passionate you feel about something, if you can’t communicate it in an enlivening or entertaining way, and if you can’t have a passion, which is the most persuasive form of communication, you might as well just not be.[vii]

The first and most critical element in the aligned organization is a compelling vision that speaks to common values and imbues all involved with the organization’s functioning with a strong sense of purpose that goes beyond personal gain.

Uniform work processes

The great enemy of customer satisfaction is variation. Consider this: we citizens of the world don’t gobble up billions of McDonald’s hamburgers due to the culinary brilliance of the grill crew or the quality of the meat. Rather, we’ve come to expect a fast, hot and predictably edible meal at an affordable price whether we’re in New York, Los Angeles, London or Paris. It’s the lack of variation that results from process uniformity that is the principal driver of McDonald’s’ success. Similarly, an insurance company that has developed a reputation for consistently delivering good service, fast claims resolution, predictable billing and excellent customer service can expect a more loyal customer base, even in the face of higher premiums. To be sure, many of the largest, most successful insurers certainly do not position themselves as low cost providers.

To achieve alignment, work processes must be performed in harmony with an organization’s larger goals. However, we often find a significant gap between even the most captivating organizational visions and the objects of their fulfillment. Peter Drucker has said that “All ideas must degenerate into work if anything is to happen,”[viii] and so we’d expect the quality of the methods by which such work is performed to be of paramount importance. Yet organizations, large and small, continue to employ ad hoc approaches to their operations; it is a standardized, efficient and effective framework for accomplishing work that is most often lacking. While the organizational leadership may have been diligent in their assessment of target markets, customer preferences and the voids which their products and services fill, they often lack a cogent means of “operationalizing” those strategies in a way that translates into the day-to-day work of employees. The realization of a leader’s strategic vision suffers most from the implementation piece – that bridge between strategy and operations that is often so poorly engineered that the thought of traversing it brings fear and trepidation. Building the proper bridge – strong, capable and proven – instills confidence in the workforce, as the solid span is easily navigated and reaching the other side a matter of routine. Uniform work processes provide that bridge.

Jack Welch famously said of GE’s programs to improve operational results, “This is the way we do things,” whether it was the Total Quality Management movement of the 1970s, the Work-Out sessions of the 1980s, or the Six Sigma initiatives that emerged in the 1990s and continue through today. Welch was emphatic about the way things got done, and as a result, decision making was made easier as those who promoted best practices at GE became true evangelists of company work processes and often rose to leadership positions within the company. Interestingly, Mr. Welch presided over the single greatest increase in shareholder value in the history of corporate America, elevating the company’s market capitalization by more than $400 billion during his twenty-year tenure as CEO.[ix]

Organizational learning

Why should work processes be uniform? Why shouldn’t individuals be left to their own devices, letting individual pockets of genius emerge as innovative means of goal attainment? The answer lies in understanding the power of organizational versus individual learning. According to Probst and Buchel, “learning by a social system cannot be equated with the sum of the learning processes undergone by individuals.”[x] Uniform work processes become the means by which an organization’s constituents get things done on behalf of the organization, and as such, the organization that succeeds in developing a uniform set of work processes develops an ability to be more adaptable to change, a key ingredient of success and longevity.

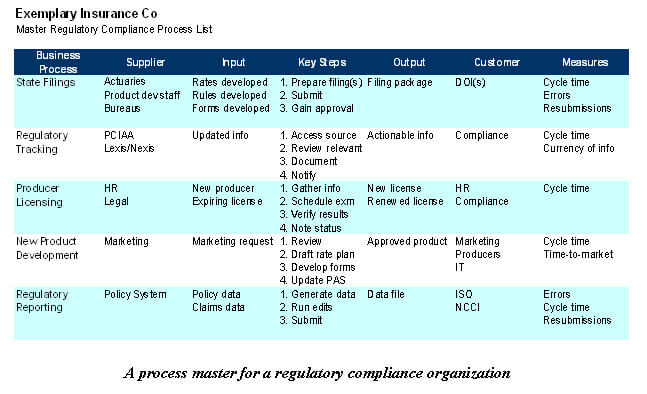

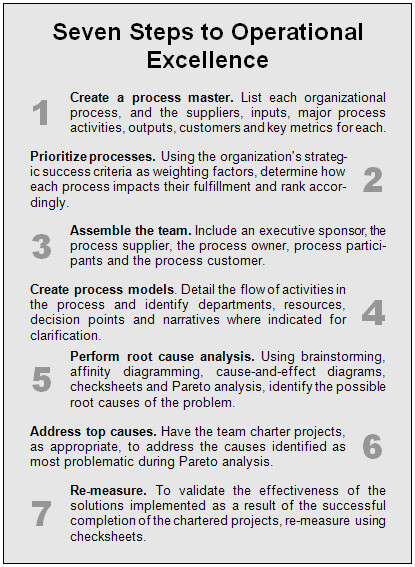

Business Process Management: A framework for uniformity

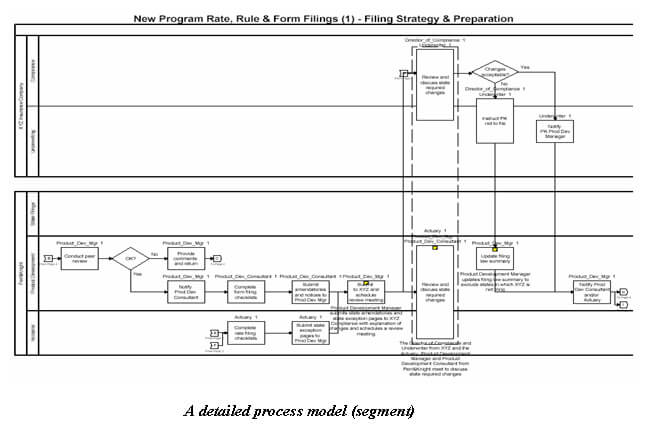

Business Process Management (BPM) is the discipline of modeling, automating, managing and optimizing a business process through its lifecycle to increase profitability. As such, it provides an excellent underpinning to a uniform process framework. A successful BPM initiative begins with the promotion of “process thinking” throughout the organization, where employees are aware of and working daily toward the improvement of the key performance indicators (KPIs) that mark the efficiency and effectiveness of – and the degree of variation contained within – the processes with which they’re involved.[xi]

Absent the modeling, measurement and monitoring of activities within the process, improvement efforts are based on guesswork and intuition. By providing so much visibility, BPM takes the guesswork out of improvement efforts, enabling fact-based decisions that deliver measurable, visible and sustainable gains. Imagine this idea extended to the dozens of processes – and hundreds of process segments – that comprise a typical insurance company’s operations. BPM provides the uniform set of tools and techniques needed to remove variation from critical operational processes, providing a solid foundation for sustainable competitive advantage.

Effective reward systems

The final component of a properly aligned organization is the system by which employees are rewarded. A major challenge of leadership is to “develop a desire within an employee to perform a task to his or her greatest ability based on that individual’s own initiative”[xii] by supporting the strength of the company vision with meaningful compensation. This means ensuring that adequate incentives are in place to motivate the workforce, or “implementing a reward system that will reinforce actions that are congruent with the new set of beliefs and values” that accompany a change.[xiii]

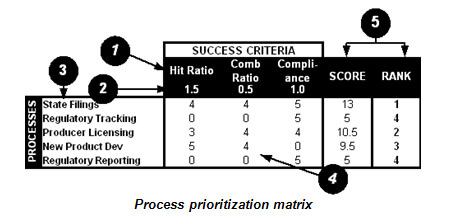

Developing a properly aligned compensation structure requires first translating the company vision into a set of success criteria. Those criteria become tangible pursuits that indicate that all in the organization are working effectively toward the fulfillment of its objectives. For example, an insurance company may determine that in order to realize its vision it must get licensed in several new states, develop and introduce new products, and provide faster claims resolution for its customers. Each of these success criteria are then quantified by assigning a target number that represents another step toward realizing the organizational vision. To be properly aligned, a portion of employee compensation is then tied to the attainment of those goals, in effect “making strategy everyone’s everyday job.”[xiv]

Benefits of alignment

History has been the best teacher. While many companies enjoy evolutionary progress in response to changing environments and the consequent needs of the organization, they often find themselves at a turning point, a point of change where calculated risks must be balanced against the collective savvy of those who lead the organization and hold responsibility for the quality of critical decisions. The stakes become higher, the job more difficult and the purposeful application of the lessons of the past never more important. True alignment helps the organization to succeed by (a) enabling genuine empowerment to take root as the adoption of well-documented best practices eliminates the propensity to micro-manage, (b) creating efficiencies by minimizing the performance of superfluous work not consistent with the larger goals of the organization, and (c) promoting effectiveness by rewarding employees for on-strategy work.

Empowerment

Empowerment is facilitated when an organization is in alignment, as the properly aligned organization makes easier the task of management by providing employees with an unambiguous purpose, clear direction and an appropriate reward system. The ability to involve employees in critical decisions enabled by proper alignment (since they are held accountable for their actions through an aligned reward system) instills trust – a critical ingredient in a culture of empowerment, while regularly disseminated performance information keeps employees aware of their standing in the organization, and the alignment of organizational interests and rewards provides tangible proof to employees that they’re doing the right thing (and doing things right).

Efficiency

Efficiency is defined by Drucker as “doing things right.”[xv] The adoption and support of uniform work processes provides for all in the organization the means to do things the right way. Absent uniformity in the way things are done, efficiency will always suffer. The adoption of proven best practices installs a comprehensive set of tools and methods to attack the work of the organization in a manner that is consistent with its larger goals, reduces process variation and provides a means for continuous improvement. The efficiencies created by the adoption of such well-established practices as those embodied in BPM, applied in every corner of the organization, will also enable a cross-functional culture to evolve as the lexicon, tools and methods common to it will begin to be used effusively throughout the organization.

Effectiveness

Drucker as well defines effectiveness as “doing the right things.”[xvi] When a dedicated workforce is rewarded for performing their daily work in a manner consistent with the larger goals of the organization, the right things get done, and the organization is as a result more effective at consistently achieving the goals it sets for itself. Consistent goal attainment is a strong motivator, as the confidence of a unified group of employees who regularly accomplish difficult objectives are filled with the benefits of effective team development, including pride, friendship, mutual support and self-esteem and develop the confidence and willingness to attack new challenges as they emerge.

Summary

As insurance companies prepare for the inevitable change that marks any dynamic industry, greater synchronization between their goals, the means by which they are achieved and the rewards available for participating in their attainment is required. To accomplish such organizational alignment, specific steps can be taken to increase the company’s chances of success:

- Vision. To create a compelling vision, first uncover common, core values by polling employees. The core purpose results from asking Why are we here? The envisioned future, supported by values and purpose, should be widely and regularly communicated by company leaders.

- Processes. To ensure uniformity in the way work gets done, the adoption of process thinking and best practices embodied in disciplines such as Business Process Management (BPM) involves extensive training and the modeling, automating and managing of key organizational processes. The enthusiastic support of leadership is critical here.

- Rewards. To directly align company vision and processes with organizational objectives, adopt a reward system that provides compensation and acknowledgement to employees who consistently perform “on strategy” work.

By taking these steps, forward-looking insurance companies stand a far better chance of attaining leadership positions in their respective market segments and achieving unquestioned organizational success.

Conclusion

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Law defines “organization” as “a body that has a membership acting or united for a common purpose.” While the definition is simple, the development of a unified, self-sustaining organization is a complex task. There are myriad means of helping to bring together a workforce for a common purpose. Cultural embedding mechanisms such as reward systems, acknowledgement, organizational structure, role modeling, and a well-articulated organizational philosophy all serve to bring people together. The basic structure critical to the organization that expects to benefit from a cohesive workforce, however, must support the efforts of employees by aligning strategies, work processes and rewards.

Alignment gives managers at every level of the organization the ability to rapidly deploy chosen business strategies, develop a world-class workforce and support a culture of continuous improvement, all at the same time. The organization that achieves alignment gains a motivated, committed group of individuals purposefully working together in a uniform manner to fulfill the vision of a compelling future – the very definition of organizational success, and the engine of sustainable competitive advantage.

References

[i] Collins, J. & Porras, J. I. (1996, September-October). Building your company’s vision.

Harvard Business Review, 65-77.

[ii] Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H. & Johnson, D. E. (2001).

Management of organizational behavior: Leading human resources (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

[iii] As cited in Senge, P. M. (1990).

The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Currency Doubleday.

[iv] Collins & Porras, 1996.

[v] Bruhn, J. (2001). Managing tough and easy organizational cultures.

Health Care Manager, 20(2), 1-10.

[vi] Frankl, V. E. (1946).

Man’s search for meaning. New York: Washington Square Press.

[vii] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2003).

Good business: Leadership, flow and the making of meaning. New York: Penguin Books.

[viii] Drucker, P. F. (1973).

Management: Tasks, responsibilities, practices. New York: Harper Business.

[ix] Welch, J. (2001).

Jack: Straight from the gut (with Byrne, J. A.). New York: Warner Books.

[x] Probst, G. & Buchel, B. (1997).

Organizational learning: The competitive advantage of the future. Herdsfordshire, UK: Prentice Hall.

[xi] Berg, R. (2007). Empowerment, productivity and profit: The promise of business process management.

Insurance News Net.

[xii] Rudolph, P.A., & Kleiner, B.H. (1989). The art of motivating employees.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, 4(5), i-v.

[xiv] Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D. P. (2001).

The strategy focused organization: How balanced scorecard companies thrive in the new business environment. (pp. 12 – 13) Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

[xvi] Drucker, 1973.

Rob Berg is a Principal and Director of Management Consulting at Perr&Knight. Over a career spanning more than twenty years, Rob has led or advised the management teams of companies in the financial services, consumer retail, software and telecommunications industries. His expertise includes strategic planning, organizational design, enterprise systems deployment, project management and process improvement methodologies, including workflow design, analysis and simulation. In addition to holding a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from Stony Brook University and completing graduate work in technology management, decision theory and organizational behavior, Rob’s practical experience is supported by credentials from the American Society for Quality (Six Sigma Black Belt) and Stanford University (Advanced Project Management).